Bones. A skull, or rather, a cranium. Long, sturdy leg bones alongside fragments of slender ones that might be from an arm. A thick, curved section that I realize is part of the spine. There are smaller, tissue-wrapped packets. I glimpse a few of the labels: TEETH and LEFT HAND and AFO. This was a person. I’ve seen and heard the term human remains at least a hundred times today. But it registers differently now. The remains of a human being who lived and breathed.

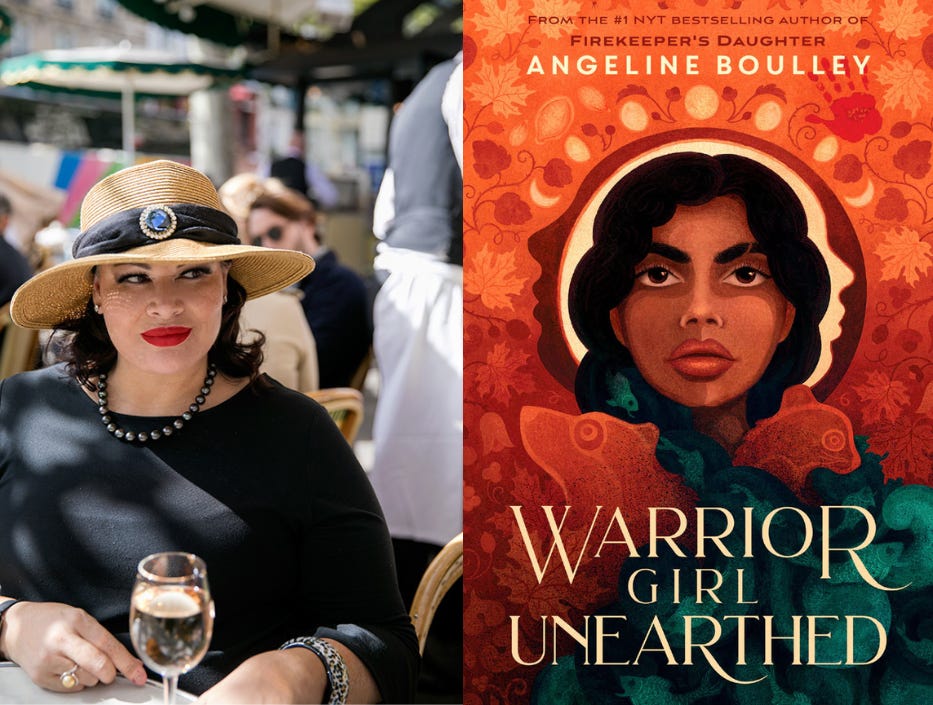

Warrior Girl Unearthed protagonist Perry, a 16-year-old member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, is at Mackinac State College, seeing for the first time, parts of her ancestors separated in boxes in the backroom of a museum. Perry is biracial and a fluent Ojibwemowin speaker with an extensive knowledge of her tribe’s history and fierce love of her community. She is enraged.

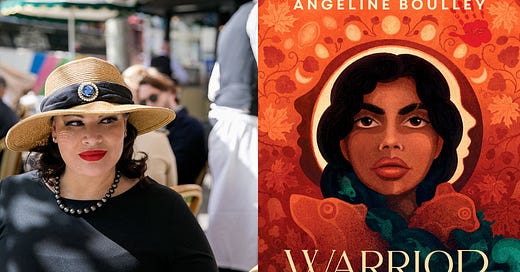

And so begins her quest to bring her ancestors back to her community for a reburial ceremony — a story Angeline Boulley (Ojibwe) crafted as an educational, thrilling and profound page-turner that left me reading late into the night. Just one more page.

Via Perry’s journey, Boulley schools us in the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990, which mandates all federally funded institutions repatriate human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony to lineal descendants and tribes. Boulley shows us the loopholes institutions have used to delay and avoid this process, using epigraphs at the start of each chapter to give context.

Here's one she includes, from a 2021 letter to Harvard written by Chief Executive & Attorney Shannon O’Loughlin (Choctaw) on behalf of the Association on American Indian Affairs:

“After 30 years of NAGPRA, you have only completed repatriation for 18.4% of the Ancestors in your collection; that means there are still 6,586 of our Ancestors and 13,610 of their burial belongings in boxes on shelves. Harvard has stolen Ancestors from at least 37 out of 50 states that represent potentially 542 of the 574 federally recognized Tribes in Indian Country today. You have significantly more deceased Native people in boxes on your campus than the number of live Native students that you allow to attend your institution (public reports state that there are 69 Native American students of more than 31,000 of your total student body).”

And another from Kathleen S. Fine-Dare, author of Grave Injustice: The American Indian Repatriation Movement and NAGPRA:

“Many of the remains of the Cheyenne men, women, and children slaughtered at the Colorado Sand Creek massacre of 1864 were sent to the Army Medical Museum … Other remains from this massacre, such as scalps and women’s pubic hair, were strung across the stage of the Denver Opera House.”

And this one:

“Do we have to be dead and dug up from the ground to be worthy of respect?”

—José Ignacio Rivera (Apache/Nahuatl)

We see through Perry’s eyes — and feel through her heart — this long and painful history of scientists, institutions and collectors who see themselves as “preserving” Indigenous artifacts for some “higher educational purpose” while in actuality, they perpetuate harm, oppression and erasure by refusing to return these stolen objects and ancestors to the Indigenous communities they claim to revere.

Running alongside this narrative in Warrior Girl Unearthed is another about the continued crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women. The Bureau of Indian Affairs estimates that there are more than four thousand cases of missing and murdered American Indian and Alaska Natives that have gone unsolved.

“I wonder how much more can be taken. I wonder how much is left for us to lose.”

— Perry Firekeeper-Birch

The book takes place in the same family and setting as Boulley’s debut novel The Firekeeper’s Daughter. She spent 10 years writing that first book — while raising three kids and working as the Director for the Office of Indian Education at the U.S. Department of Education. It was an overnight success and #1 NYT bestseller.

When asked why she thinks her book was so well-received in this interview with The Reading Culture, Boulley says in part because there is growing recognition of the need to decolonize — or, Indigenize, as she prefers — the canon of young adult literature. She says people are finally starting to get how important it is, “telling a story about a biracial mixed-heritage teen from the perspective of someone who is that and knows the nuance of it.”

“I love my community and I think you can only write about it if you love it — because I do tear apart tribal council leaders! We have unpleasant truths in our communities. But I know where to draw that line and I know that our community is more than our trauma. So the humor, the role of elders… all these wonderful things I feel like someone outside my community trying to tell a story about my community would only see the surface of.”