This is part three of a series; here’s part one (What I Didn’t Say) and part two (Emotionally Ghosted)

I stared at my wet bathing suit draped over the back of a chair. It was the morning after I had the dream and we were packing up, preparing to move our stuff to my mom’s house before spending the day with my dad’s side of the family.

I was having a hard time gathering myself, let alone my belongings. I scanned my dad’s dining room table. Damp towel. Sundress. Goggles. Hat. Stack of books.

What goes where?

What do I need?

What do I wear?

I just stood there.

My family bustled around, getting the baby’s things together, tidying the kitchen. I felt guilty I wasn’t contributing, dreaded that my paralysis would make us late. But I couldn’t help it; it was like the messages in the dream — especially the suggestion that I’d felt emotionally ghosted by my dad — I had yet to process clogged up my whole being, trapping me in slow motion.

I managed to stuff everything in a couple bags and get in the car. I sat still in the backseat, as if any abrupt moves might dislodge the clog and I’d drown. When we arrived at my mom’s, I stepped into my room to try to collect myself. I sat on the bed knowing it was time to go, that we’d be late to my grandma’s, but I couldn’t move.

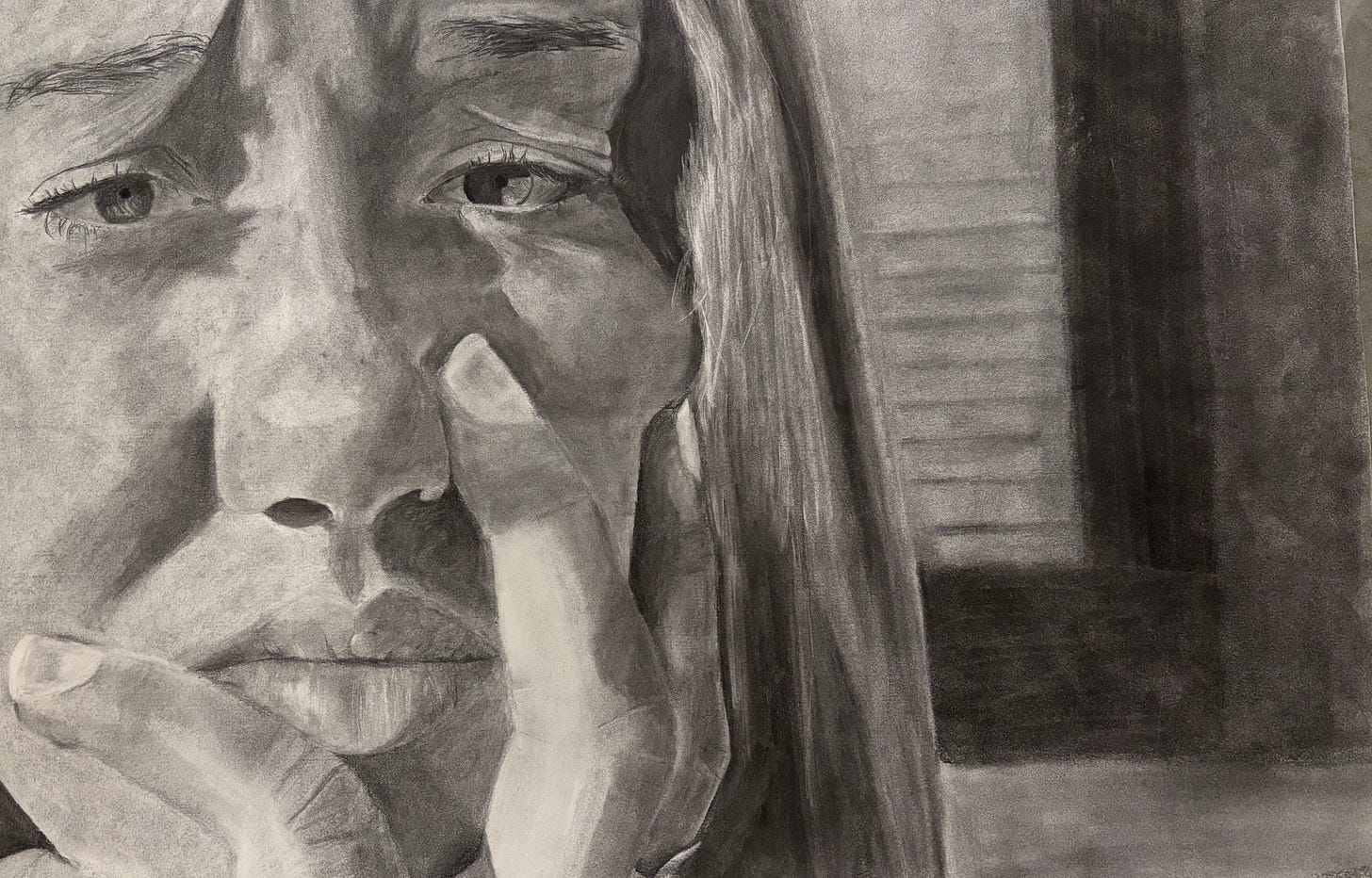

Finally, in that moment alone, the dam broke. At some point my mom came in and sat with me while I cried. Then my brother knocked softly. “You can come in,” I managed.

He wrapped his arms around me and I sobbed into his shoulder. “Shhhhhh, shhhhhh, shhhhhh,” he breathed into my ear, comforting my inner six-month old like he’d learned to comfort his baby son. It’s okay, his shhhh said, you’re going to be okay. I stopped trying to find reasons, to make sense, and just let the emotion pour.

I opted out of the family gathering and took refuge in the woods that border my mom’s farm — climbed into my hammock strung between two birch trees and drifted off.

I awoke heavy with guilt for missing this precious time with my brother and his family, who were only visiting for a week. I berated myself for not being able to pull it together — what was there to be THIS upset about?

… I feel I’m also being dramatic and making stuff up about how bad it was when it wasn’t that bad… I wrote in my journal post-nap.

I’ve been well-schooled in suppressing/minimizing/denying my Big Emotions. It’s a collective strategy we use to keep ourselves and everyone around us from facing the shit.

You’re being dramatic

You’re making stuff up

It wasn’t that bad, we say.

Because it’s fucking terrifying to go to the depths.

There in the hammock, I remembered the card I pulled on one of my first evenings in Michigan: Death reversed. In my deck (Mother Peace), the illustration shows a skeleton in the fetal position at the base of two birch trees, surrounded by a shedding snake. This card represents transformation: letting go, breaking down so a new state of being can emerge. Reversed, according to my deck: “…she holds onto a dead form, she may not be ready to let go. She may feel numb or stuck.”

There I was between those two birch trees, trying to close the dam right back up. My denial was preventing me from continuing to release this pain to the earth to decompose.

But I’ve struggled beyond this before, learned to let the feelings be as intense as they are, to honor them as messages from parts of myself that need to be heard. I try to remember that my pain — and that of generations past that I carry — deserves my attention; whether it’s “worse” or “less intense” than anyone else’s doesn’t matter. It’s my responsibility to tend.

So I kept writing.

… but maybe it’s about seeing how much my dad is barely capable of now and how little that means he was capable of when he was self-medicating and after the fact. Maybe it’s just hitting at a deeper level.

When I watched my dad playing with his baby grandson… it looking like he was trying so hard, like he was learning in real time how to be vulnerable and express love openly. I had been struggling to call up memories of him being that way with other kids, animals, or my mom throughout my childhood.

And there in the hammock I started to let the deeper cause of my torment sink in, the one being revealed through my dream: for much of my early years, he hadn’t had the capacity to be this way with me.

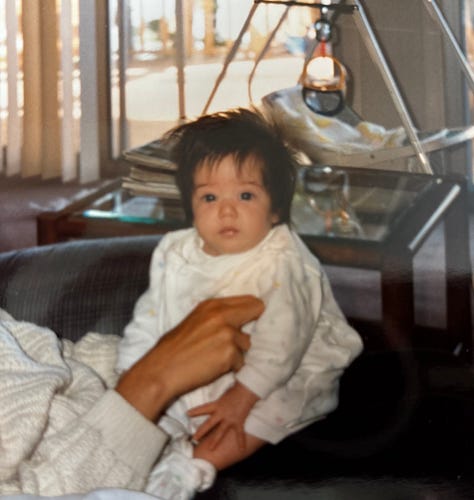

For the first five years of my life, my dad was addicted to pain killers. He was stealing Tylenol with codeine from the pharmacy where he worked and managing to hide it from everyone. Not even my mom knew. From the outside, he was “there” and everything was “normal.” Until my mom caught him grabbing a pill from his stash hidden behind a peg board in the garage, which spurred his journey to sobriety. (To make a very long story short.)

Up until a few years ago, the narrative in my family was something along the lines of:

Thank god dad got sober when you were only five years old,

Thank god you kids don’t have memories of that time…

I inferred: thank god it didn’t affect you.

Until my late 20s, I believed the narrative — that I got away unscathed. That I was lucky.

… and it’s true, I am lucky. That my dad was present in so many ways, that he was able to get sober and stay clean. That he showed up and loved us how he could despite his undealt-with pain from his own childhood (in an alcoholic family) working against him.

It’s also true that during my most tender years, he was in a grueling oscillation between floating numb above my childhood home and craving another dose, while perpetually stressed about getting caught.

I try to remember that my pain — and that of generations past that I carry — deserves my attention; whether it’s “worse” or “less intense” than anyone else’s doesn’t matter. It’s my responsibility to tend.

I know because we’ve talked about it, him and I. Since I started therapy in 2021, we’ve had quite a few conversations. I’ve asked him to share what it was actually like — how he actually felt during those early years — so I could more deeply understand how it actually was. So I could weave stronger threads of truth into the story my family had written in self-protection.

Over the years, he has grown in his capacity to be honest with himself and with me about our past. And I thought that — through our conversations, therapy and releasing floods of tears — I had made sense of it, healed this wound.

But my nephew was here to show me a deeper layer.

In his blue eyes I saw a baby’s deep capacity to see, to search for connection. I began to imagine my little self in that search, looking into my dad’s blue eyes —30 years younger — waiting for feedback, for resonance. I imaged her learning as a toddler to scan those eyes, to read their level of intoxication, their degree of presence, in a nanosecond. I imagined her frequent struggle to pull them from drifting, from vacancy.

I imagined how she yearned to be held in a gaze of deep presence, love and protection.

That little me needed to stop trying to be okay, stop putting on a good face for the family. She needed to be held by the birch, the ash and the maples. She needed the love of her cousin who drove up to be with her. She needed to be rocked in the hammock all day with her tears.

She needed to grieve.

…. stay tuned for part 4

❤️🩹

there is so much here that resonates; and after reading there's always a desire to simply pause and reflect. As always, thanks for your voice and for reminding us of how powerful words are.